A World on Debt: Who Pulls the Strings, Who Pays the Price, and How States Lose Sovereignty

The world no longer runs on money. It runs on debt. States no longer govern; they roll over liabilities. Budgets are no longer built; they are patched. And when the truth surfaces, we are told it is "normal": every country has debt, markets demand confidence, international institutions provide stability. But in observable reality, debt is not just a financial instrument. It is a mechanism of control.

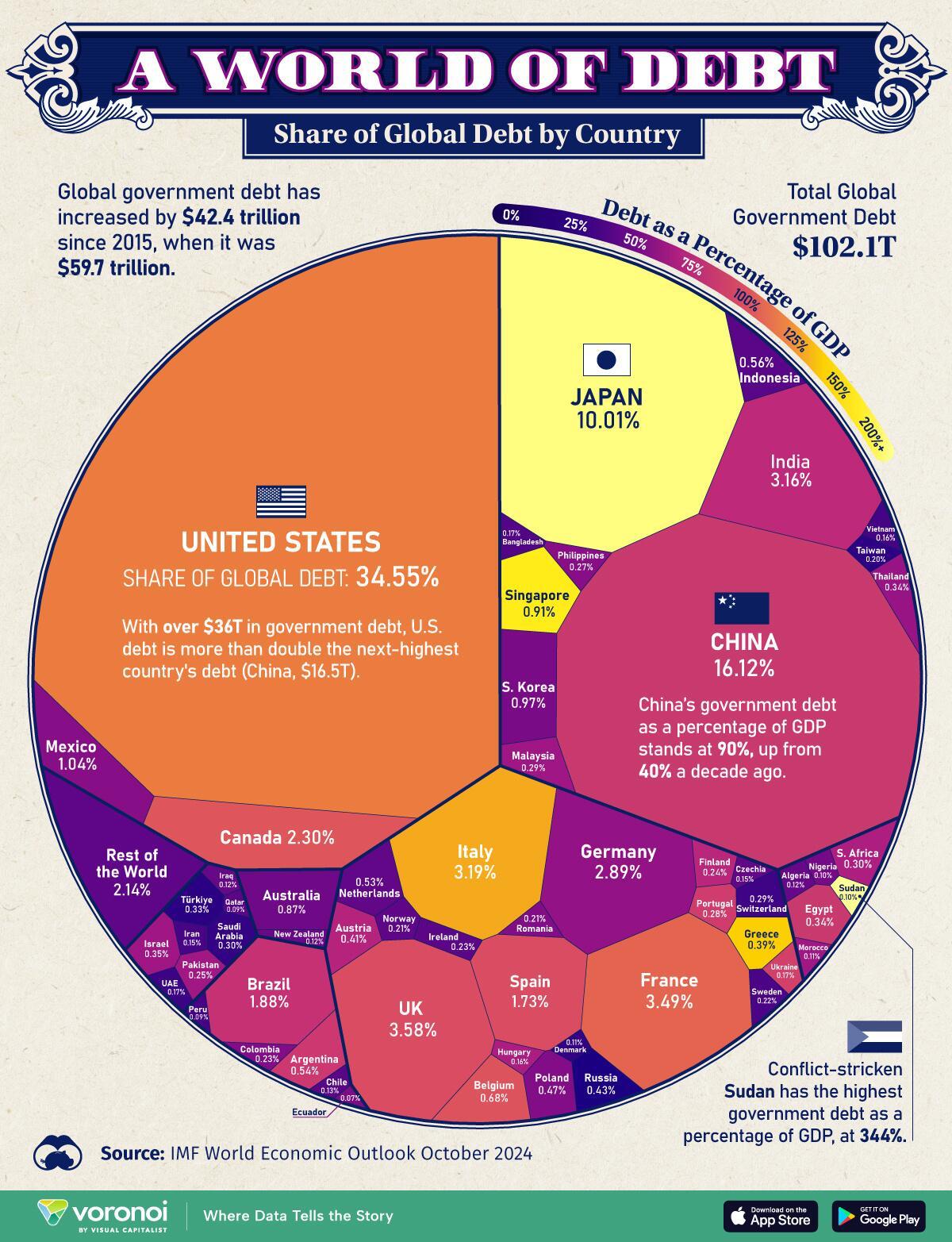

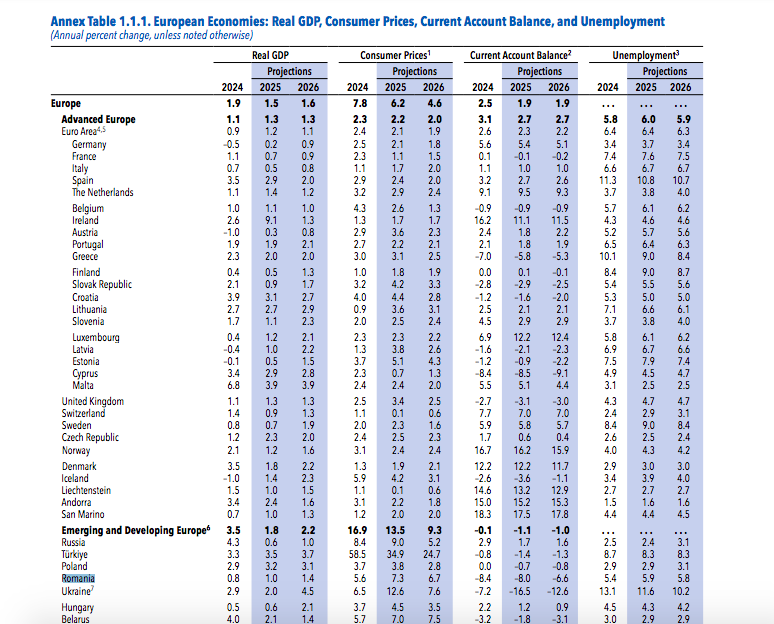

According to the IMF (World Economic Outlook - General Government Gross Debt, October 2025 edition), global government debt remains at historically extreme levels, while advanced economies exceed thresholds that would once have triggered alarm. At the same time, IMF Global Debt Monitor 2025 shows that indebtedness does not disappear-it shifts, restructures, and embeds itself deeper into state policy. External debt across developing economies is mapped through instruments such as the World Bank's International Debt Statistics and joint datasets maintained by the BIS, IMF, OECD, and World Bank. The system tracks everything. The question is: for whose benefit?

In the modern financial architecture, the so-called "puppet masters" are not a secret council in a dark room. They are mechanisms: banking networks, bond markets, interest rates, credit ratings, multilateral institutions, conditionality frameworks, and governments that accept debt as destiny. Once a state enters the spiral, it no longer sets direction. "Markets" decide. "Ratings" decide. "Programs" decide. "Adjustments" decide. The population pays-through taxes, inflation, wage freezes, and the erosion of public investment.

The justification for debt is always the same: crisis, development, investment, emergency, security. In practice, the causes follow recurring patterns: oversized states, rigid expenditures, captured budgets, institutional corruption, inflated contracts, import dependency, lack of competitiveness. When these collide with shocks-pandemics, energy crises, wars-borrowing becomes reflex. Then habit. Then dependency.

The largest and most geopolitically significant example is the United States. According to IMF WEO data and U.S. federal statistics, America holds the largest public debt in the world. The question "to whom?" reveals the global nature of the system: a massive share is held domestically (institutions, funds, the central bank), while according to U.S. Treasury data and Congressional Research Service summaries, the largest foreign holders include Japan, China, and the United Kingdom. This is not conspiracy-it is strategic reality: those who finance hold influence, even when that influence is invisible.

Below is a compact map of public debt levels (as share of GDP, IMF series) and dominant creditor types: domestic (banks/funds), market-based (bonds), multilateral (IMF/World Bank), bilateral.

The Debt Map: Countries, Levels, and Creditor Types

United States - very high; creditors: domestic + foreign (Japan, China, UK) via Treasury bonds.

Japan - extremely high; creditors: overwhelmingly domestic (banks, funds, households).

China - high; creditors: mostly domestic, significant local-government opacity.

France - high; creditors: EU markets, ECB, institutional investors.

Italy - very high; creditors: domestic banks, ECB, external investors.

United Kingdom - high; creditors: funds, banks, global investors.

Germany - high; creditors: domestic and international markets.

Spain - high; creditors: ECB and financial markets.

Canada - high; creditors: domestic and foreign investors.

Australia - high; creditors: international markets and domestic funds.

Greece - very high; creditors: EU/ECB programs, historical IMF conditionality.

Portugal - high; creditors: ECB and EU investors.

Belgium - high; creditors: EU markets.

Netherlands - moderately high; creditors: markets and financial institutions.

Austria - high; creditors: EU markets.

Poland - moderately high; creditors: markets and EU-linked institutions.

Romania - rising; creditors: bond markets, banks, EU institutions; refinancing dependence.

Hungary - high; creditors: markets, selective bilateral loans, EU exposure.

Czech Republic - moderate; creditors: mainly domestic and market-based.

Bulgaria - moderate; creditors: domestic and markets.

India - high; creditors: predominantly domestic, supplemented by external markets.

Brazil - high; creditors: domestic markets and external investors.

Mexico - moderately high; creditors: international markets.

Turkey - high; creditors: foreign banks and markets; currency vulnerability.

South Africa - high; creditors: markets and external investors.

Argentina - chronically fragile; creditors: IMF and bondholders; repeated restructurings.

Pakistan - vulnerable; creditors: IMF, multilaterals, bilateral lenders including China.

Egypt - vulnerable; creditors: IMF, Gulf states, markets.

Ukraine - wartime vulnerability; creditors: EU, U.S., IMF, World Bank.

Venezuela - prolonged default; creditors: bondholders, bilateral lenders, commercial litigation.

This list could continue almost indefinitely, because the model is global. There is no "indebted country." There is an indebted system. Within it, debt becomes an invisible chain: governments change slogans but preserve refinancing dependence. Policy is written for the next bond issue, not the next generation.

This is where the apocalyptic tone comes from-not because the world ends tomorrow, but because it enters an order where real sovereignty is conditional. When you owe, you accept rules. When you accept rules, you accept control. When control is normalized, you are told there is "no alternative." That is the most dangerous captivity of all: one presented as normality.

The final question is not "who is guilty?" in a cinematic sense, but: who benefits when states become debt-dependent, populations are disciplined through austerity, and politics is reduced to accounting management? Where benefit is consistent and cost is public, there is a pattern. And in geopolitics, patterns are never accidental.

0 Comments

There are no comments on this article.